Directed By: Josh Cooley Written By: Stephanie Folsom & Andrew Stanton Starring: Tom Hanks, Tim Allen, Annie Potts, Tony Hale, Christina Hendricks Call me a cynic, but it really is an unnecessary tempting of fate… More

Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again

Directed By: Ol Parker

Written By: Ol Parker (based on the musical Mamma Mia! by Catherine Johnson)

Starring: Lily James, Pierce Brosnan, Stellan Skarsgard, Colin Firth, Amanda Seyfried

A Mamma Mia movie is like one of those shamelessly campy Bond films of the seventies and eighties, the ones in which the heroines had names like Ocotpussy and the bad guys were horse riding, blimp flying test tube babies built by the KGB: hardwired to withstand exorbitant terribleness. Like those Moore era Bonds and like the songs around which its narrative orbits, a Mamma Mia movie just has something in its genetic code that lends it unique Teflon like abilities; it could never be too bad, so long as it in one way or another proved entertaining.

But therein lays the problem. Mamma Mia 2: Here We Go Again is kind of dull. As it happens a shamelessly reverse engineered plot in which the story consists entirely of contrivances aimed at contextualising the singing of what, to these novice ears, sounds like ABBA’s B-side cast-offs (the group’s essentials were used up in the prior movie) can only be so engaging.

To backtrack, the film itself is a musical in which a selection of ABBA numbers comprise the soundtrack and thus, in theory, much of the narrative thrust. The plot doubles in function, ala The Godfather Part 2, at once serving as prequel and sequel, recounting on one hand how a freshly graduated Donna (Lily James) first came into contact with the three young men who would become so central to her life (Jeremy Irvine/ Pierce Brosnan, Josh Dylan/Stellan Skarsgard, High Skinner/Colin Firth) whilst on the other in present day Donna’s daughter Sophie (Amanda Seyfried) combats disastrous weather and relationship trouble en route to the grand re-opening of her mother’s coastal hotel in Greece (thus concluding any and all viable Godfather comparisons.)

It seems redundant to say the plot is more flimsy connective tissue between prescribed musical numbers than it is any sort of framework for character or story, a concession any reasonable movie goer will be happy make. This is big screen karaoke, better understood through the lens of an animated juke box than through the prism of traditional cinema. What’s problematic however is that said plot, in the shameless transparency of its machinations, can’t help but smack of an idleness and corporate cynicism which constantly threatens to undercut the efforts expended by the film’s effervescent cast. What should be innocuous transitions into vibrant musical set-pieces become alarm bells indicating that behind every step and off-key note is a studio riding the 600-million-dollar wave of Mamma Mia’s initial big screen outing a decade prior. What’s that? We’re in a Napoleon themed café? Close enough’s good enough, cue Waterloo. I can’t believe it, that character’s name was actually Fernando this whole time? That’s unlikely, and handy. It’s a routine which gradually drains the film of its colour.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t traces of charm to be found in the luminousness of the cast. Lily James, embodying Donna’s free-spiritedness with equal parts juvenile vitality and elegance, heads an ensemble that is evidently eager to launch into ABBA’s catalogue with a self-deprecating glee. Pierce Brosnan is either thankfully or regrettably (depending on one’s affinity for comical self-punishment) relieved from singing duties, but still clearly relishes the lunacy of the whole exercise, whilst his non-musical compatriots in Colin Firth and Stellan Skarsgard cheerfully follow suit to infectious results. Julie Walters and Christine Baranski provide a cheeky sense of bad-influence sorority to the film, with the latter, armed with the film’s crudest tongue, serving as a too disparate reminder of Richard Curtis’ influence from behind the keyboard (Curtis is credited with contributing to the story.) Curtis’ trademark amalgamation of crudity and earnestness rears its head through the material just long enough for us to realise what might have been.

It’s peculiar that Ol Parker’s screenplay opts to splinter the cast, isolating them from each other for extended portions of the film and refusing to marshal them into the same space until too late in the piece. In the end, it is the cast’s collective energy which supplies the skeleton for Mamma Mia’s off-kilter sense of spectacle—there’s simply just not as much fun to be had in watching these stars on their own. If the Avengers movies have taught us anything, it’s that there is an inherent cinematic thrill in seeing a hefty collection of larger than life personalities operate in close proximity—a thrill that Parker curiously leaves untapped (thus concluding any and all viable Avengers comparisons.)

What the screenplay’s mismanagement of the cast cannot detract from the performers however is their absolute benevolence — the hurricane of goodwill they generate which in turn encapsulates the niceties and total liberality that Here We Go Again employs as its pillars. Regardless of whatever financial motivations might be lingering over the action, the cast is evidently there to have fun. Combined, they lend an air of purity to Here We Go Again, anchoring proceedings in amiability, even when those proceedings are at their most pedestrian.

Is an acute friendliness enough to redeem the myriad deficiencies to be spotted elsewhere? I can’t say it is. Friendliness and fun aren’t one in the same, and Here We Go Again spends too much of its time on autopilot to be genuinely fun. At most the film packs enough to persuade us to stick around until the end of the track, but it might be time to stop feeding this juke box money.

Rating:

1.75/4

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

Directed By: J.A. Bayona

Written By: Derek Connolly and Colin Trevorrow

Starring: Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Rafe Spall, Justice Smith, Daniella Pineda

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, just like its immediate predecessor (Jurassic World,) is to no small extent an allegory for its own making: a bottom-line issued revival of a past wonder; a bigger, technologically flashier, but ultimately shadowy imitation of a prior concept; an ill-disciplined exploitation of the central, prehistoric creation; a financial juggernaut propagated by talented yet misguided artists who refuse to learn from the mistakes of their antecedents.

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, just like its immediate predecessor (Jurassic World,) is to no small extent an allegory for its own making: a bottom-line issued revival of a past wonder; a bigger, technologically flashier, but ultimately shadowy imitation of a prior concept; an ill-disciplined exploitation of the central, prehistoric creation; a financial juggernaut propagated by talented yet misguided artists who refuse to learn from the mistakes of their antecedents.

To be fair to Fallen Kingdom (directed by J.A Bayona) the film is not all doom and gloom, indeed it may even be the strongest of all Jurassic Park sequels; it dares to journey to corners less travelled before it eventually consigns to its fate as a nearly brainless monster flick.

Written by Colin Trevorrow (director of Jurassic World) and Derek Connolly, Fallen Kingdom is the fifth Jurassic movie, and the first to genuinely put a spin on the reoccurring subtext which underscores each of its predecessors. Where the franchise’s prior instalments all circled the idea of man’s desire to play God and the follies of that hubris, Fallen Kingdom skews towards dialogues that might have been at home in a Phillip K. Dick novel— philosophical enquiries into the validity of synthetic life: are the lives of the dinosaurs (built in labs) worth less than the lives of the world’s natural fauna? Do humans have a moral obligation to protect the very species that they de-extinguished against nature’s will? Should we let nature take its course in rendering these creatures extinct once again (in the form of an impending volcanic eruption which is threatening to consume the now dilapidated island of Isla Nublar following the events of Jurassic World) when it was us humans who meddled in nature to begin with? These are intriguing questions, so intriguing that the franchise’s most colourful personality is called upon to weigh in on them—the all too briefly returning Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum,) offering his eccentric genius at a senatorial hearing on the matter.

The fact that the film is never entirely sure of how to grapple with its own ethos—Trevorrow and Connolly’s screenplay ultimately conflates its enquiries into the validity of synthetic life with enquiries into when, if ever, the will of nature is to be questioned—is secondary to the fact that there are even ideas to be conflated in a franchise’s fifth episode. But if one thought that Bayona and the screenplay from which he is working would be able sustain such intellectual ambition for the duration of the picture, sadly, they would be wrong.

That’s not necessarily a deal-breaker. Spectacle is the true currency of the Jurassic saga; even Spielberg’s masterful original ultimately dropped its ideas in favour of chase sequences and theatrics. So how does Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom deliver on that altogether bawdier front? Partially is the answer, but it begins with a lot promise.

Trevorrow and Connolly find a way to legitimately raise the quotient of spectacle from the gargantuan levels rendered by Spielberg in 1993. Commissioned by Benjamin Lockwood (dinosaur lover and former John Hammond associate, played by James Cromwell) Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard) and on-again-off-again beau Owen Grady (Chris Pratt) return to Isla Nublar (a ragtag team of military men and tech experts—geeky and sassy alike—in toe) to shepherd what remains of the marooned dinosaurs to safer territory.

What ensues is the standard Jurassic Park fare in which measly humans are pursued by roaring, destruction-thirsty reptiles, culminating in a string of millimetre tight disaster aversions. This time, however, it’s all complimented by the eye-catching addition of volcanic explosions, a marriage as bombastic as it is genuinely intoxicating; it’s Steven Spielberg meets Irwin Allen, a monster movie PLUS a disaster movie.

It’s a one-two punch of spectacle just crazy enough to work, even if the extraneous, non-dino calamity threatens to distract from the creatures that rightly still comprise the bedrock of the film. But if one thought that Bayona and the screenplay from which he is working would be able to sustain such levels of intoxicating roller-coaster verbosity, sadly, they would be wrong.

What ought to constitute the film’s finale, with brazen set-pieces including a partially paralysed Chris Pratt attempting to slither away from encroaching lava, a neurotic I.T nerd clumsily attempting to escape a T-Rex by scaling a ladder to a jammed door, and more than one death defying plummet from a cliff’s edge, is instead relegated to first act pyrotechnics.

The crux of the action rather transpires in a basement at Lockwood’s Californian estate, where unbeknownst to him, his assistant Eli (Rafe Spall) is orchestrating a black-market auction of the world’s remaining dinosaurs.

It’s a decidedly less epic arena than that which has housed these creatures in the past, and whilst one can spot the potential novelty in a haunted house twist on the action where raptors roam corridors instead of ghouls, it’s a setting which lacks the deserved majesty to befit its prehistoric inhabitants, and a setting which in the process constricts the dinosaurs to the role of faceless action movie participants.

Spielberg’s original movie framed its creatures with towering grandiosity and reverence; it understood their mere presence on screen could supply a cinematic thrill, with the director distilling as much awe from a Brachiosaurus munching on a tree branch as a T-Rex violently pursuing a jeep full of panicked bodies. Fallen Kingdom doesn’t seem to trust its dinosaurs to deliver the requisite spectacle on their own, instead feeling compelled to have them crash through walls and battle caricature militants as though they were more Jack Reacher than reptile to get the job done, a process which gradually bleeds the dinosaurs of personality and presence alike. With each passing Jurassic movie the inherent wonder of the dinosaurs goes less and less tapped, as though the filmmakers, like their arrogant human subjects, have lost the respect they ought to have for their prehistoric counterparts.

A similar fate befalls the film’s human characters. Pratt and Howard, whilst individually luminous, struggle to conjure the romantic chemistry their dynamic so sorely needs, a platitude heightened by the papery personalities they’ve been assigned in which their characters can be summarised with a single trait: he’s a maverick, she’s a sympathiser.

Chomping the scenery with his eye-smelting teeth and Trumpian hair, Toby Jones bring as much panache to proceedings as his similarly one-dimensional villain allows, whilst Daniella Pineda and Justice Smith, playing giddy and fear-stricken visitors to the island respectively, supply a wavering pulse of energy.

Bayona’s work behind the camera also manages to conjure a wavering pulse of its own, the director exhibiting genuine flashes of a craftsman’s penchant for theatricality. Bayona’s calibrated use of shadow and his subtle patience for waiting on a set-piece, playing on his audience’s anticipation with finesse, validate that with greater assurance in the subjects, Fallen Kingdom might have served as a genuine pop-corn thriller worthy of the title from which it derives. A tableau of cineliteracy drip-fed throughout the action further hints at Bayona’s craftsman abilities; visual allusions to Nosferatu, and most substantially the Jurassic saga’s original work helps to develop a fleeting glimpse of affection that never quite permeates the action as it might have, and indeed, should have.

The whole thing inevitably feels shackled, caged and confined like the dinosaurs themselves, longing to burst free and exhibit their true potential. For all of Bayona’s flair, and for all of Trevorrow and Connolly’s philosophical riffing, one can’t help but feel that Fallen Kingdom’s finer qualities were destined to suffocate under the film’s true, corporate preoccupations, a preoccupation doubly difficult to transcend given the film’s allotted role of bridging piece—the mere obligatory connective tissue to join the two truly salient parts of the saga. After all, if one thought that J.A Bayona’s direction, and the screenplay from which he worked wasn’t ultimately geared towards the next Jurassic instalment rather than geared to delivering the goods in its own right, sadly, they would be wrong. That’s the sort of cynical money first mentality that would have Ian Malcolm quavering in his boots—the film’s producers too preoccupied with whether they could, that they never stopped to think whether they should.

Rating:

2.25/4

The Incredibles 2

Directed By: Brad Bird:

Written By: Brad Bird

Starring: Holly Hunter, Craig T. Nelson, Sarah Vowell, Huck Milner, Samuel L. Jackson

At a glance The Incredibles 2 seems poised to serve as a hotbed of discussion for all things current. A world in which the ubiquity of superheroes is lamented rather than celebrated? Watch out Marvel. A feminist twist on narrative norms in which a middle-aged mother fights crime whilst her husband changes diapers: take note antiquarians. A culture in which people are more concerned with the content on their screens than the content of their character: perhaps we’re all a little guilty on that front. There’s a lot of contemporality on the table, but outside of a courteous tip of the hat and a slight nod, The Incredibles 2 winds up being more defined by a brawl between a baby and a racoon than any true leaning into reality, and that’s not such a bad thing.

At a glance The Incredibles 2 seems poised to serve as a hotbed of discussion for all things current. A world in which the ubiquity of superheroes is lamented rather than celebrated? Watch out Marvel. A feminist twist on narrative norms in which a middle-aged mother fights crime whilst her husband changes diapers: take note antiquarians. A culture in which people are more concerned with the content on their screens than the content of their character: perhaps we’re all a little guilty on that front. There’s a lot of contemporality on the table, but outside of a courteous tip of the hat and a slight nod, The Incredibles 2 winds up being more defined by a brawl between a baby and a racoon than any true leaning into reality, and that’s not such a bad thing.

Deadpool 2

Directed By: David Leitch

Written By: Rhett Reese, Paul Wernick and Ryan Reynolds (based on the comic book Deadpool created by Fabian Nicieza and Rob Liefeld)

Starring: Ryan Reynolds, Josh Brolin, Julian Dennison, Zazie Beetz, Morena Baccarin

Withstanding the hypocrisy of a film touting its reflexive send-ups of the ubiquitous comic-book blockbuster’s clichés, whilst itself indulging those same clichés, the first Deadpool signalled a blindsiding overachievement. Armed with an overdue performer in Ryan Reynolds— who had finally found his cinematic soulmate and through him broke not only the fourth-wall, but also the shackles—Deadpool parlayed the abandon and irresistible smarm of its titular anti-hero from the humble origins of a comic-book outlier, into the deformed face of an 800-million-dollar sleeper hit of proportions so atmospheric in height, that a sequel was rendered obligatory before the box office receipts could even be tallied.

Withstanding the hypocrisy of a film touting its reflexive send-ups of the ubiquitous comic-book blockbuster’s clichés, whilst itself indulging those same clichés, the first Deadpool signalled a blindsiding overachievement. Armed with an overdue performer in Ryan Reynolds— who had finally found his cinematic soulmate and through him broke not only the fourth-wall, but also the shackles—Deadpool parlayed the abandon and irresistible smarm of its titular anti-hero from the humble origins of a comic-book outlier, into the deformed face of an 800-million-dollar sleeper hit of proportions so atmospheric in height, that a sequel was rendered obligatory before the box office receipts could even be tallied.

The first time Ryan Reynolds donned that red and black latex in a film of his own, enough acerbic wit, intoxicating juvenility and belligerent reckless abandon was supplied to discern an illusion of genuine subversiveness. Deadpool beared the same mechanical inner-workings as every Marvel movie it purported to flip off, but it was also savvy enough to figure it might as well satirise those mechanics whilst they were in operation. Does being conscious of one’s crimes make said crimes any less criminal? I don’t believe it does, but Deadpool validated that if you can offer enough laughs along the way, one might just forget to punish those trespasses.

And now we get that obligatory sequel, which, to surmise, is a proper sequel, through and through. That is to say Deadpool 2 does the thing that corporately mandated successors so often do— eschewing the novelty of the original for an extra helping of whatever worked the first time around (replete with recycled jokes), except with a greater degree of bombast and a slightly inflated cast list.

There are more explosions in Deadpool 2, more set-pieces, more characters (Zazie Beetz’s Domino—who boasts luck as a superpower—being the worthiest addition,) more meta, more C words…and overall less fun to be had.

To the film’s credit there’s more of an attempt at heart too. The organising notion of Deadpool 2 is the instillation of humanity in our protagonist. It’s a plot born out of tragedy: Wade Wilson, for the first time since his power bestowing surgeries, has been lastingly wounded, catalysing the emergence of his long-veiled inner altruist. It’s an emergence which leads him to 15-year-old Russell (Julian Dennison, star of Hunt for the Wilderpeople), an orphaned, pyrotechnic mutant monikered “Firefist” who is in dire need of affection. It’s a quest which also leads Deadpool into combat with the militant, time travelling Cable, played with joke-begging inter-Marvel-movie villainy by Josh Brolin, whose sibling performance as Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War does not, it seems redundant to say, go unmentioned.

The most subversive element of Deadpool 2 is the desire from director David Leitch, renowned for his craft of action (John Wick, Atomic Blonde,) and the trio of screenwriters (Mr Reynolds himself, and the returning duo of Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick) to bring Deadpool to ground level; subversive at least, per the prior Deadpool’s standards. There’s sentimentality in this film, an allegedly family-friendly morality at its core, where wars are more effectively waged with love than with splattering violence (not that the splattering violence has been skimmed.) “Your heart is not in the right place” Wade is cryptically warned by wife Vanessa (Morena Baccarin), a notion which Leitch and company set about unpacking and rectifying— coupling sanguine and sentiment, profanity and profundity.

It’s an admirable pursuit, but the scabrous, blood-bathed irreverence which made the first Deadpool such an uncompromising hit proves infertile soil for such sincere growth of character. Deadpool is hardwired for comedy, and it’s when the comedy is on centre stage that the film comes closest to recapturing its initial magic.

The first Deadpool, in spite of budgetary constraints and a tirade of higher-up scepticism, somehow felt liberated, as though it was free to march to whatever beat it wished. Wade Wilson and co obliterated fourth walls, undermined their own cinematic compatriots, dowsed the screen in crudity and gore, and had an evidently great time doing it. To the sequel’s detriment, that rough-edged liberality now feels more calibrated than organic. Those winking meta jabs are delivered less out of serrated satire than they are adherence to a winning formula. There are laughs in Deadpool 2 to be sure, but the presiding tone isn’t so much one of gloriously unchecked freedom, and more of bottom-line issued imitation. The wit is less acerbic, that juvenility less relished, that abandon less authentic, and soon those in-gags signposting CGI fight scenes and those references to the property’s franchise prospects start to play less like attempts at brazen humour, and more like bashful confessions.

The film does grow into its stride during its second half (beginning with Deadpool’s recruitment of the ragtag “X Force” to aid him on his journey to redemption,) the film opening up its comedic outlook to move beyond the overabundant imitative in-gags of the first act, and incorporate the physical comedy and giddy immaturity which contributed so substantially to the original movie’s novel scent.

It’s not until the final credits however that Deadpool 2 truly hits its comedic peak, taking aim at the eponymous character and the star that plays him by means savage and clever. It’s the sort of no-holds-barred humour that birthed Deadpool in the first place, and a reminder of what has been lost now that the series has caught the corporate eye. Sure, an amplitude of good intentions are employed to cater for any cynicism—attempts at pathos, an extra helping of spectacle (the extra 60 million dollars in budget is enshrined in the film’s bolstered action,) the efforts to bring us into Deadpool’s headspace. But that cynical waft proves inescapable, and good intentions never really were Deadpool’s style.

Rating:

2.5/4

Isle of Dogs

Directed By: Wes Anderson

Written By: Wes Anderson

Starring: Bryan Cranston, Ed Norton, Live Schreiber, Greta Gerwig, Koyu Rankin

There is one inevitable question which lays at the core of every Wes Anderson film. Can the humanity of the story withstand the artifice of the style?

Anderson’s surgical tendencies have long toed the line between charming and wearisome. There is an undeniable degree of craftsmanship in the work; every frame of every film feels as though it was whittled with a scalpel from a block of wood and then strummed into a living, breathing dollhouse. The arrangements are impossibly symmetrical, the details fiercely obsessed upon, the air scented with an idiosyncratic waft of artificiality which infects the humour to quirky reward, but which, more problematically, has the inclination to infect characters too. Isle of Dogs is an example of the more troubled breed of Anderson film, Continue reading “Isle of Dogs”

Annihilation

Directed By: Alex Garland

Written By: Alex Garland (based on the novel Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer)

Starring: Natalie Portman, Oscar Isaac, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Tessa Thompson, Gina Rodriguez

What comes next after pulling apart the distinctions between human sentience and A.I sentience? Surely pulling apart the distinctions between human beings, nature, time, and the universe as we know it.

Alex Garland’s 2014 directorial debut Ex Machina, by means as exhilaratingly visceral as they were intellectual (as is the penchant of the best science fiction cinema), honed in on sexuality and ego to brilliantly collapse the emotional boundaries delineating humans from their artificial counterparts. Not one to take a backwards step, for his next existential musing (Annihilation) Mr Garland has dropped us in the sort of trippy milieu that sci-fi lives for—“the shimmer” as it’s known in this particular instance— an ever-expanding alien ecosystem growing out of the U.S’ Southern coast which many have entered in the vain hope of unlocking its mysteries, but from which only a single soul has ever returned.

Oscar Isaac is that soul, a military man named Kane who arrives back at home after a year of MIA to meet his weeping wife (biologist Lena who had assumed him dead, played by Natalie Portman) in the bedroom the two used to share—or has he? Something is evidently off. To any questions Lena logically asks, Kane can only respond “I don’t know”, words we’ll hear often throughout the film—a telling refrain for a film that so courageously refuses to place its viewer on steady ground.

There are very few certainties offered in Annihilation, but what we do know is that “the shimmer”, after Lena teams with four other women as part of a research expedition earmarked for the alien territory, is a sub-world populated with all manner of impossibly cross-bred flora and fauna. It’s an arena through which Mr Garland audaciously deconstructs the boundaries between humanity and nature, (like he did humans and androids previously) commenting along the way on man’s inextricable bond, and thus obligation to, his environment. That would be one reading at least. Perhaps what Alex Garland is actually commenting on is humankind’s propensity for self-destruction; or perhaps he’s commenting on the notion that evil is predicated on difference; or, more simply, on the randomness of the universe; I can’t say for sure, nor could anyone, which is tantamount to the film’s success.

Annihilation isn’t short on boldness then, tossing up as many questions as it does gut-wrenching thrills, and underlining it all with an ostentatious ambiguity. I can’t tell you a great deal about what happens in the film, partly of course because of spoilers, but chiefly because it’s just not possible. To borrow Winston Churchill’s description of Soviet Russia, Annihilation is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma— a film that is as compulsively watchable as it is intellectually evocative, taunting us with its incessantly cryptic demeanour as though it’s daring us to extract our own morality and meaning from the spectacular, immersive, macabre tableau it presents.

It’s difficult to banish thoughts of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, or, from more recent times, Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! when viewing Annihilation, films which make similar use of ambiguity to both stimulate and herald a perverse funhouse effect— Garland’s enigmatic narrative is an exhibition in sustained unease; to watch Annihilation is to feel as though you have woken from a walking slumber inside a blackened house in which you’ve never been before.

It’s not all seamlessly executed. It’s one thing for a film to champion dread, it’s another to eschew humanity for portent. What troubles Annihilation is that it succumbs to its own severity and strains for profundity to enrapture us as fully as Lynch’s or Aronofsky’s best.It’s a portentousness which comes to plague the film’s characters as much as its narrative, the mutually damaged quintet of women who embark on the expedition (alongside Portman stands Tessa Thompson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez and Tuva Novotny) are each so brooding and joyless that they inevitably make for pretty miserable, and, more problematically, tiring company. These characters can’t help but pale in interest compared to their mission.

But what Annihilation lacks in humanity it more than caters for in intrigue— a stunning exercise in white-knuckle suspense, bolstered by Garland’s keen eye for arresting visuals; his alien world a catalogue of stunning vistas and Frankenstein-like creatures as malevolent as they are striking, all lensed by Ex Machina photographer Ron Hardy who amalgamates elegance with ghostliness.

And anchoring it all is that challenge which Garland so daringly insists upon, the director urging us to feel our way through his film’s ethos, to find our own way to our feet after he has whirled us away and hurled to the floor in the most unfamiliar of settings, as though he were some Kansan hurricane. Alex Garland doesn’t merely task us with finding the answers, he tasks us with finding the questions, allowing Annihilation to provide the one-two punch that streams through only the most ambitious and effective science fiction thrillers— socking the stomach whilst sparking the mind.

Rating:

3/4

Black Panther

There are a string of inevitabilities tethered to every new instalment in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Vast box-office receipts are a guarantee (Marvel has accumulated such a devoted fanbase that any director could sleepwalk to a three-hundred-million-dollar hit.) An elite, top-of-its-game ensemble is another. There’s a level of quality control too, below which it has become seemingly impossible for Marvel’s cinematic projects to sink below.

tethered to every new instalment in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Vast box-office receipts are a guarantee (Marvel has accumulated such a devoted fanbase that any director could sleepwalk to a three-hundred-million-dollar hit.) An elite, top-of-its-game ensemble is another. There’s a level of quality control too, below which it has become seemingly impossible for Marvel’s cinematic projects to sink below.

But flip the coin and one will find less flattering inevitabilities: a certain element of beaten path adherence, of structural routine and formula as sure-fire as a Stan Lee cameo, and the forever looming fear that each MCU instalment has the prescribed fate of dazzling fleetingly before consigning to the role of a cog in the larger machine.

How could each individual stroke of the brush not be awash in the larger canvas, when said canvas is this dense? We’ve had eighteen MCU movies now, all in quick order. Sure, James Bond has had 24 instalments, but at least they’ve been spaced out over nearly 60 years. Marvel’s self-produced series of movies have all come in less than ten.

The question then, is how a director can leave their fingerprints on a cinematic cosmos that dwarfs any one person. Taika Waititi made a valiant effort with his kinetic, off-kilter comedy in Thor: Ragnarok. James Gunn fared even better with his unabashedly nostalgic treatment of Guardians of the Galaxy (both volumes.) But no one has accomplished that unenviable task to the degree of Ryan Coogler, who, with Black Panther, has made for mine the finest MCU movie yet.

Here is a film that feels alive and new, paying its debts to the larger franchise that houses it, whilst standing discerned upon its own two feet. More than a Marvel movie made by Ryan Coogler, Black Panther is a Ryan Coogler movie made with Marvel resources, touting a look, sound and centricity on character that begets unprecedented shades of originality in this ever-expanding cinematic tapestry.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Coogler is such a fine fit for the job— he’s both a natural custodian of the onscreen black experience (an integral ingredient of Black Panther’s unique identity; never has a superhero movie immersed itself in black culture as this film does), and a natural at breathing fresh life into seemingly exhausted material, ala Creed.

Where the fresh life in that prior movie manifested itself in a staggering cinematic flair, an injection of new personalities and a reconfiguring of old ones however, Black Panther’s manifests itself in the grafting of an entirely original landscape that is populated with faces that are as engaging as they are pleasantly unfamiliar.

Wakanda is the setting, a third world African country to the naked eye, but one that underneath its guise is the most advanced nation in the world. The cornerstone of Wakanda’s secret advancement is vibranium, the most valuable, dexterous material in the world which happened upon the Wakandans via a meteorite crashing into their turf some centuries ago, and which the natives have subsequently laced throughout their technology and infrastructure to build a super civilisation.

And it’s a pretty cool civilisation to look at. Think of Wakanda as Earth’s very own Asgard, rife with shimmering neons and labyrinths of towering skyscrapers, interspersed with stretches of lush green mountainsides and cascading waterfalls. It’s a sleek futurism carefully imbued with parcels of ancient Africana, where the tribal and space-age cross; an indelible blend. Imagine Blade Runner meets David Lean meets Madagascar. And the soundtrack follows suit, Ludwig Goransson’s score niftily underlining contemporary hard-edged hip-hop with primitive tribal rhythms. Even at base level, this is a film with a flavour all its own.

One element that is somewhat familiar is the Black Panther himself, who we first brushed shoulders with in Civil War. Chadwick Boseman plays T’Challa, the man inside the suit and assumer of Wakanda’s throne, continuing Marvel’s implacable habit of note-perfect casting. Boseman serves as a model of quiet nobility and understated intensity in the title role, whilst lightly dashing that steely demeanour—“I never freeze” T’Challa tells his sister before embarking on an assignment, insulted he wold have his level-headedness queried—with the faintest traces of vulnerability as he grapples with his new duties as head of his people.

Boseman mines considerable vitality from T’Challa, but the truth is there isn’t all that much to the character outside of his proficiency in combat and his wrestles with Kingship. A less intelligent screenplay mightn’t have known exactly what to do with him. Thankfully Coogler, who co-wrote Black Panther with Joe Robert Cole, does. Together the two writers open-up their narrative’s field of vision to situate T’Challa in the drama not as a focal point, but as a central figure in a larger ensemble populated with characters who can each command the story when needed.

Letitia Wright plays Shuri, T’Challa’s kid sister and the Q to his Bond, running circles in the tech-savvy stakes around even Marvel’s own Tony Stark. She’s also a perennial scene stealer, her firecracker energy and budding sass allowing her to own the camera at will.

If Shuri’s the brains, then fellow women Nakia and Okoye offer much of the brawn. Lupita Nyong’o and Danai Guirira play the warriors respectively, the former a spy and T’Challa’s ex-lover, the latter the head of Wakanda’s special forces unit, both bearers of a finely tuned moral compass and a penchant for bad-assery. These are women not to be messed with, and characters who Coogler isn’t afraid to task with much of the story’s heavy lifting. No need for assistance from the likes of Tony Stark and Steve Rogers here.

Daniel Kaluya (Oscar nominated for Get Out) has a more volatile moral compass, torn by his duty to Wakanda and his malice for colonialists. But no one intrigues more than Michael B. Jordan’s Killmonger, Marvel’s most compelling villain to date, a fierce warrior in his own right who invades Wakanda to irreparably up-end the nation’s status quo.

Rare is the action film that extends its villain this degree of empathy. Not only is Killmonger a viable threat to our heroes, but he’s also a man with an ethos and a scheme born out of an understandable logic. It’s certainly true that the violent means outweigh the end, but this is an end that, at least in small part, is to be sympathised with, ushering with it a racial consciousness that film’s of this nature seldom have the nerve to hold—a complete subversion of the evil for evil’s sake antagonists even Marvel’s most thoughtful writer’s so regularly resort to.

Not since Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy has a comic-book film so seamlessly reconciled blockbuster and art-house sensibilities; has a filmmaker reconciled their own artistic ambitions with their studio’s. If there’s one demarcating factor for Black Panther, it is that; that breadth of vision, that scope of character, that leaving an auteuristic impression on a film that is inherently corporate in conception. Black Panther, more than a box-office venture or a precursor to the next Avengers movie, is a Ryan Coogler film; a sophisticated character study with its hands and feet locked in moral considerations. Black Panther is also as much the new MCU benchmark as it is a watershed moment for the genre in all. Suffice to say, Infinity Wars has its work cut out for it.

Rating:

3.75/4

Obligatory Oscar Prediction Blog Post (2018)

With the Oscars only days away, and now that all of our major award show indicators are out of the way, I suppose it’s time for another obligatory Oscar Prediction Blog Post in which I endeavour to get inside the Academy’s head and forecast who will take home what is alleged to be cinema’s top prize.

Before I do, as always, it’s worth stating that awards and art aren’t always the most natural bedfellows. As many have said before (most recently Sam Rockwell who is earmarked for his own Oscar this year,) there’s no rational way to determine who is objectively the best in a form where everyone is striving towards a different goal, is appealing to different tastes, and was created under different circumstances.

Movies aren’t like sports, in which competitors aim to cross the line first or score the most points, and if they do then it reasons to stand that they were fundamentally better. How can you put a wordless performance like Sally Hawkins’ from The Shape of Water against a towering, diatribe-laden exercise in fierceness like Francis McDormand’s turn in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and say who did it best. Did what best? They were asked to do different things. If you truly wanted to gain an objective insight as to who did it best, you would have to get 5 actors/actresses to play the same exact role and evaluate from there. And even then, it’s still a matter of taste. Come to think of it, why do the Academy even segregate men and women in the acting categories? They don’t in any other field, and last I checked biology has little to do with artistic merit. But that’s beside the point.

Irrationality aside, I can’t pretend I don’t love watching the Academy Awards, cheering on my favourites to win and spitting the dummy when they don’t. If nothing else, at least the Oscars give us a reason to celebrate movies, and it gives me another reason to talk about some of 2017’s best films.

Lady Bird

Directed By: Greta Gerwig

Written By: Greta Gerwig

Starring: Saoirse Ronan, Laurie Metcalf, Lucas Hedges, Timothee Chalamet, Beanie Feldstein

There’s a beautiful line about midway through Lady Bird in which a paper, written by

There’s a beautiful line about midway through Lady Bird in which a paper, written by

our eponymous character, is remarked upon by the school principal as showing a great love and care for Lady Bird’s much maligned hometown of Sacramento. “I guess I pay attention” Lady Bird replies, playing cursorily polite contrarian. “Don’t you think they’re maybe the same thing?” the gentle and wise Sister replies. “Love, and attention?” It’s the chief insight in a film teeming with insights, each gorgeous and evocative in their own unique way. It’s also a notion which permeates the making of Greta Gerwig’s solo writing and directorial effort, as much as it does its in-story dogmas.

Greta Gerwig is someone who has obviously paid close attention in life, to the people and settings which have shaped her. We know this because there is a stunning perceptiveness to her filmmaking, a raw humanity that brims with affection for the world, even as it mocks the inscrutable characters and abundant injustices, big and often small, which comprise it.

Like Annie Hall and Boyhood before it, you’d swear that Lady Bird was an autobiographical work, that it’s events were lifted from Ms Gerwig’s own personal diary, so rich and full and steeped in specificity they are. I’m not sure exactly how autobiographical Lady Bird is, there are certainly basic overlaps between the life of the protagonist and the life of her creator that are apparent (Catholic school, Sacramento, a gravitation to the arts, the period in which they cusped on adulthood—the film is set in 2002.) But what’s certain is that lushness of detail is there indomitably, paving the way for an emotional honesty that films rarely attain. It also allows Lady Bird in the process to effortlessly exceed the coming-of-age Hollywood trappings its screenplay flirts with.

The rhythms of fiery, angsty, self-contradictory 17-year-old Christine McPherson’s life (aka Lady Bird, played to perfection by Saoirse Ronan) aren’t all that different from the litany of coming-of-age undertakers before her. There’s the obligatory contrived strain for identity, hence the ardent rejection of her birth name—“Lady Bird? Is that your given name?” one teacher asks of our on-again-off-again heroine. “Yes. It was given to me by me.” There’s the boy trouble, firstly in the form of the neat and well-to-do nice guy harbouring hidden troubles (played with poignance by Lucas Hedges); and then in the form of the not-so-nice and fantastically pretentious Kyle (Timothee Chalamet) who reads literature as he sits upon car hoods and laments society’s enslavement to technology and capitalism. There’s the bid for popularity at the expense of one’s true self, where Lady Bird opts to trade in her most trusted compatriot Julie (a bubbly innocent played by a luminous Beanie Feldstein) for a bitchier, sleeker, more socially accepted model (Odeya Rush). There’s the episodic familial spats, which run cyclically and predictably, like they’re tuned to a clock; and the inevitable, unenviable task of planning for adulthood, chiefly expressed here as Lady Bird applies for East Coast colleges, hoping they’ll be her means of liberation from the monotonous drear that is Sacramento.

These episodes are ostensibly familiar, but Gerwig’s delicate nature and generosity of spirit breathe unique life into them. They are not so much bumps on Lady Bird’s road to coming-of-age, as they are their own overlayed miniature movies, chapters which play out not sequentially, but concurrently. Most films adopt a structure in which they firstly arrange their pieces, build the tension, then conclude with the emotional release. Lady Bird is a film in which all of life is happening all the time, each episode rendered with its own emotional peaks and valleys, its own brand of indelible wisdom, its own gut-punching, heart-tearing, uproarious emotional catharses. Those episodes are also comprised of their own ensembles, Gerwig looking beyond Lady Bird’s field of vision to pay those who surround her a level of attention that Lady Bird herself so often neglects to extend.

I wish I could rattle off a list of the film’s key moments and lines, the big and the small, like when Lady Bird’s melancholic, unemployed father (Tracy Letts) offers the most minute but loving gesture of selflessness to his son at a moment crucial to both of them; or when the school drama teacher initiates an exercise with his students to see who can cry first, like he’s searching for a context in which he can let it all out; or when Julie informs Lady Bird, with poetic succinctness, that not everyone is built happy. Not wanting to be too selfish, I’ll stop there. What’s salient is that Lady Bird has a stunning breadth of soul and heart that will at times sweep you up in waves and leave you crumpled on the floor, and at others will whirl you into a joyous frenzy where you’ll want to scream it all out of your system to the sky, much like Lady Bird herself does when she shares her first kiss.

The through-line in the narrative, the constant article, is Lady Bird’s turbulent relationship with her mother Marion (Laurie Metcalf, every bit as perfect as Ronan), a nurse who works double shifts to keep her family’s collective heads above water. When we first see Marion and Christine together they are sharing tears over a John Steinbeck audio book. Mere seconds later Christine would have hurled herself from a moving car to escape her mother’s diatribes—this relationship is beyond volatile, liable to explode even out of the calmest breath.

The two clash over most everything—college applications, finances, clothing—with a toxicity born out of their similarities, cut from the same fiery, headstrong cloth as they are. These are also two decidedly imperfect people; fascinating about their dynamic is that Gerwig never feels obliged to give either the higher moral ground. They can be cruel, unsympathetic, they regularly say the wrong thing at the wrong time. Marion is overcritical. Christine is nasty. They wound each other. “I wish that you liked me” Lady Bird says to her Mum as she’s trying on dresses for prom. “Of course I love you” Marion replies. “But do you like me?” is Lady Bird’s anguished response. One senses that if these two didn’t live in such close quarters they might have been the best of friends, but as it stands their affection for each other subsides in an unexpressed love that underlines their union palpably. They’re profoundly flawed, and thus profoundly human, with Ronan and Metcalf bringing an untempered honesty and truthfulness to their so often unflattering roles, without ever alienating us from their charms.

Together, Ronan and Metcalf are embodiments of Lady Bird’s magic—unapologetic, real, wryly funny, sometimes poetic in their insights (without ever tipping into scripted Hollywood artifice), but always irresistible. It’s those qualities which make Lady Bird not just a quietly original coming-of-age dramedy (no mean feat), but one of the season’s absolute highest achievements.

Rating:

4/4

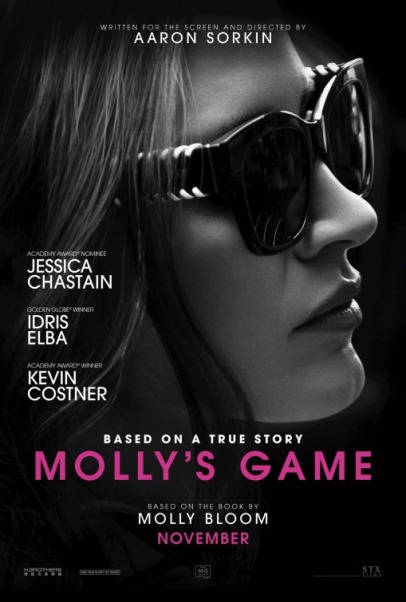

Molly’s Game

Directed By: Aaron Sorkin

Written By: Aaron Sorkin (based on the memoir Molly’s Game: From Hollywood’s Elite to Wall Street’s Billionaire Boys Club, My High-Stakes Adventure in the World of Underground Poker by Molly Bloom)

Starring: Jessica Chastain, Idris Elba, Kevin Costner, Michael Cera, Jeremy Strong

It’s perhaps no great surprise, or  critical insight, to remark that Aaron Sorkin directs like he writes. Aaron Sorkin is a man who lives and dies by the power of the spoken word—he champions it as the foremost tool in any dramatic arsenal, and he inhabits that ethos with a fullness of force that gives way to an apparent phobia of silences.

critical insight, to remark that Aaron Sorkin directs like he writes. Aaron Sorkin is a man who lives and dies by the power of the spoken word—he champions it as the foremost tool in any dramatic arsenal, and he inhabits that ethos with a fullness of force that gives way to an apparent phobia of silences.

It’s a familiar if timeless routine by now (assuming it’s performed correctly)—acerbic wit, total breathlessness, punch, panache, and an excess of energy. Sorkin’s alacritous style works for many (Emmys for The West Wing— an Oscar for The Social Network) and is just as surely a great frustration to others. I find myself somewhere in between, Continue reading “Molly’s Game”