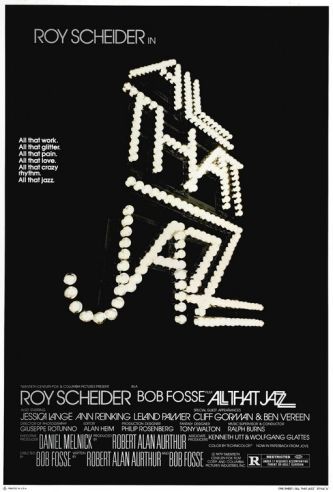

Directed By: Bob Fosse

Written By: Bob Fosse and Robert Alan Aurthur

Starring: Roy Scheider, Jessica Lange, Leland Palmer, Ann Reinking

All That Jazz is a fascinating, cross-thr eaded character portrait of two men who exist in different universes; one man exists in front of the camera, the other behind it. The story revolves around a workaholic hedonist named Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), an chain-smoking adulterer, theatre director/choreographer and moviemaker who, tellingly, forever puffs away at a cigarette which seems to be expiring all too quickly. “To be on the wire is life” Joe narrates at the beginning. “The rest, is waiting.” The accompanying visual sees our narrator plummet from a tightrope to a safety net below, the delicate balancing act a reference to Joe’s teetering between two high profile showbiz gigs, on one hand frenetically piecing together his new Broadway musical, on the other painstakingly editing his upcoming movie The Stand-Up. Joe, however, is really the indiscreet surrogate for All That Jazz’s real life filmmaker Bob Fosse; the stage show is the obvious stand-in for Chicago, the Stand-Up for Lenny, both acclaimed productions which were helmed by Fosse who is now attempting to purge his shortcomings as a person during this period through a film about a selfish artist never more than a missed breath away from himself expiring.

eaded character portrait of two men who exist in different universes; one man exists in front of the camera, the other behind it. The story revolves around a workaholic hedonist named Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), an chain-smoking adulterer, theatre director/choreographer and moviemaker who, tellingly, forever puffs away at a cigarette which seems to be expiring all too quickly. “To be on the wire is life” Joe narrates at the beginning. “The rest, is waiting.” The accompanying visual sees our narrator plummet from a tightrope to a safety net below, the delicate balancing act a reference to Joe’s teetering between two high profile showbiz gigs, on one hand frenetically piecing together his new Broadway musical, on the other painstakingly editing his upcoming movie The Stand-Up. Joe, however, is really the indiscreet surrogate for All That Jazz’s real life filmmaker Bob Fosse; the stage show is the obvious stand-in for Chicago, the Stand-Up for Lenny, both acclaimed productions which were helmed by Fosse who is now attempting to purge his shortcomings as a person during this period through a film about a selfish artist never more than a missed breath away from himself expiring.

Like Woody Allen seemed to do with Annie Hall, Fosse wrestles his own faults to the ground and confronts them with a steely frankness. Joe Gideon is promiscuous and shameless. He sleeps around, never short of female bodies to keep him company, even chatting-up an Angel of Death in some softly lit, imagined space, Joe’s literal flirting with death another none-too-disguised metaphor for his trajectory. In reality, there are three long-suffering women in Joe’s life, his ex-wife Aubrey (Leland Palmer,) his girlfriend Katie (Ann Reinking,) and his daughter Michelle (Erzsebet Foldi), each of whom equally neglected by a man who can only keep himself ticking through a morning concoction of cigarettes, eye drops, and a prescription drug cocktail. Fosse has no illusions about himself. He knows that for every instance of his genius, is an instance of his failure as a man. He refuses to shy from his talents, but at times All That Jazz feels like a flamboyant exercise in self-hatred, a vicious case of introspection, where Joe’s obsessive mulling over his work, longing to eradicate every crinkle and crease in his art, mirrors a haunted Fosse who longs for the final cut of his own life, where events can be tinkered retrospectively and shaped until there can be no regrets, a notion  which Fosse recognises to be, through Joe’s insatiability, a pipe dream.

which Fosse recognises to be, through Joe’s insatiability, a pipe dream.

There’s irony in the idea that Fosse’s purging himself of his real-life inability to know when enough is enough, is in itself a rather indulgent practice. If Fosse were to make an episode of 60 minutes, it would last two hours, however the director has such a sure grip on the cinematic art form that his rambling challenges the tightest constructions from the most disciplined filmmakers for vitality. Consider the scene where Joe and his Broadway cast perform a table read, everyone around him howling with laughter in mute. The soundscape is instead reserved for Joe’s wrapping of his fingers on the table, the scraping of his chair on the floor, the lighting of his cigarette; every motion Joe makes is protracted, every sound amplified, honing in on him uncomfortably as every movement signals a fight to keep his head above water. Fosse finds unique ways to allow Joe’s dizziness to become our own. All That Jazz is made with such a manic bravado and unhinged spirit that Fosse’s peering into his own mind moves beyond the picking apart of a psychology, and transforms into a visceral, head-spinning experience. It’s not enough to tell us about his life, Fosse recreates the near nauseating stupor of it, aided in no small part by Alan Heim’s impeccable editing which carries a burlesque musicality of its own. Heim’s accelerated cutting plays like a symphony composed entirely of whip cracks, whilst Fosse navigates the full-throttle narrative of his existence like a pilot attempting to barrel roll their way out of a hurricane.

The language in which Fosse is best versed is naturally the language of theatre. The most revelatory moments of All That Jazz come through elaborate, extended song and dance numbers; a sweltering, sexually loaded rehearsal for Joe’s stage-show  embodying his lusty appetites; a cute duet between Katie and Michelle which brings to life Joe’s capacity for affection; and, most memorably, a lengthy passage in which Joe is confined to a hospital bed, capped by a spectacular epilogue taking the form of a variety show special where Joe performs for those who have shaped his life throughout the film.

embodying his lusty appetites; a cute duet between Katie and Michelle which brings to life Joe’s capacity for affection; and, most memorably, a lengthy passage in which Joe is confined to a hospital bed, capped by a spectacular epilogue taking the form of a variety show special where Joe performs for those who have shaped his life throughout the film.

It would be too easy to forget Roy Scheider in all of this, an actor playing very much against his factory-setting of the understated everyman. An unobvious choice though Scheider appears to be, you cease seeing an actor perform against his propensity quickly. Instead, Scheider too breathes great life into the chaos of the picture, he disappears into Joe, one look into his face is all one needs to know this is a man on the brink of calamity.

For many viewers, All That Jazz is a case of Fosse trying to rationalise his infidelity and narcissism, to pose the question to his viewer, “how could you blame me?” I don’t think Fosse particularly cares what evaluations people may make of him from watching this film. Rather, I sense he made this film for his own good, a vehicle through which he can lay his own character out on the table so he can come terms with it; more sanity project than vanity project. The benefit for us is that it hurls us into a lifestyle that few of us could imagine; a head-spinning, gut-swirling, riveting (if not rambling) spectacle that allows us to be much more than a mere fly-on-the-wall.