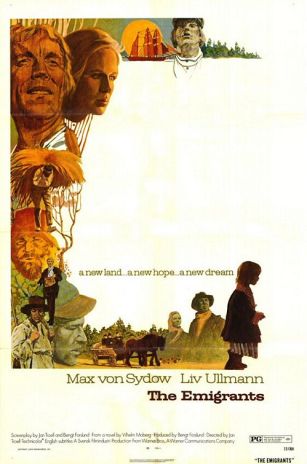

Directed By: Jan Troell

Written By: Bengt Forslund and Jan Troell (based on the novel The Emigrants by Vilhelm Moberg)

Starring: Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann

The Emigrants is a true epic. It’s long, its narrative sprawls and stretches, it’s heavily populated, and it covers a net of ideologies as broad as the terrains travelled by its central voyagers. This is a film about faith, resolve, family, naivety, determination, unity and disillusionment.

Specifically it’s about a family of near impoverished farmers in mid 19th century Sweden who, finally beaten by the harsh conditions which foil their crops, determine to emigrate to Minnesota, a land supposedly designed for farmers.

Jan Troell’s Best Picture nominee calls to mind a compatriot of the same year, Martin Ritt’s Sounder. The obvious affinity is the narrative concerned with scrapping low class croppers, but the salient parallel is in the films’ matter-of-fact approach to their subjects.

Troell is unflinching in his depiction of the tribulations that plague his central family. He is also unrelenting. There is seldom a scene which doesn’t browbeat the weary Nilsson family further, but Troell doesn’t wallow in the family’s plight. The film doesn’t pander for sympathy or lose sight of the humanity that is at its heart. The suffocating struggle of this life is never lost on us, but it’s never exploited either. In a distressing sequence, one of the daughters of the Nilsson’s eldest son Karl Oscar (Max on Sydow) is lost to a burst stomach, and hardly a tear is shed before he starts work on her coffin. It’s this dead-eye gaze into a series of mounting hardships that make the family so admirable. They persist without a pause for pity.

The tribulations manifest themselves in a static lifestyle rather than in blood and tears. The reluctant chugging of youngest son Robert (Eddie Axberg) and his fellow farmhand Arvid (Pierre Lindstedt) is spliced with the tinkering and ticking of Arvid’s pocket watch, giving their fight a sense of futility; time elapses but they remain stagnant. It’s a notion punctuated by Troell’s slow fading cuts and images dissipating into darkness, as if to suggest a weary and reluctant resignation.

The film’s le ngth is both an asset and a detriment. Its 190 minutes allows for an authentic passage of time. It allows us to admire the steeliness of the protagonists, their perseverance and desperation. However the film isn’t as absorbing as it ought to have been. It’s because, much like the lifestyles it depicts, the narrative flow itself feels stagnant. The film often feels lethargic if not real. The chills of the savage Swedish winter are numbing, the cycle of backbreaking physical labour is wearisome, the central battlers of Karl Oskar and his wife Kristina (Oscar nominated Liv Ullman), in another comparison to Sounder, are wonderfully grounded in their survival of a common struggle, (they remain brave and affectionate but never shy away from the pain and anger through which their life is characterised). It is an entirely sensory film, to watch it is, in a strictly immersive sense, trying, yet its capacity to affect seems to plateau after the first 90 minutes of watching a family cyclically take one step forward, then two steps back.

ngth is both an asset and a detriment. Its 190 minutes allows for an authentic passage of time. It allows us to admire the steeliness of the protagonists, their perseverance and desperation. However the film isn’t as absorbing as it ought to have been. It’s because, much like the lifestyles it depicts, the narrative flow itself feels stagnant. The film often feels lethargic if not real. The chills of the savage Swedish winter are numbing, the cycle of backbreaking physical labour is wearisome, the central battlers of Karl Oskar and his wife Kristina (Oscar nominated Liv Ullman), in another comparison to Sounder, are wonderfully grounded in their survival of a common struggle, (they remain brave and affectionate but never shy away from the pain and anger through which their life is characterised). It is an entirely sensory film, to watch it is, in a strictly immersive sense, trying, yet its capacity to affect seems to plateau after the first 90 minutes of watching a family cyclically take one step forward, then two steps back.

Empathy is not beyond the film’s range. The ceaseless war for merely an opportunity is an involving one which dodges sentimental traps, and the hopefulness which glimmers in the eyes of Karl Oskar and Robert, imagining a land free of classes where the soil is always fruitful, is both charming and saddening. These are true, proletariat warriors. There are many moments of beauty too. When Karl Oskar finally shakes hands with the vicious Ulrika (Monica Zetterlund) the film glows with a warming humanity, a humanity which all but justifies Troell’s lumbering approach.