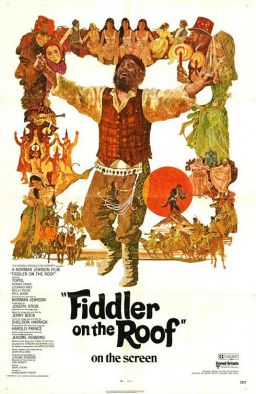

Directed By: Norman Jewison

Written By: Joseph Stein (based on the Broadway Musical Fiddler on the Roof and the short stories Tevye and his Daughters by Sholem Aleichem)

Starring: Chaim Topol, Norma Crane, Leonard Frey, Molly P icon, Paul Mann

icon, Paul Mann

The triumph of Norman Jewison’s previous Best Picture nominees has been his ability to reconcile. With The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming he masterfully reconciled screwy comedy and gentle humanism. With In the Heat of the Night Jewison lassoed together police procedure and race relations. The latest Broadway comedy-drama come Oscar nominee Fiddler on the Roof requires more of the same from its director, looking to combine genial character and a much darker socio-political edge. Jewison isn’t as up to the challenge as he has been previously, but that isn’t to say there aren’t joys to be had in his film’s resilient affability.

The story concerns reconciliation too. Set in early 20th century Russia, the narrative focuses on a small Jewish community isolated from that of the principal Christian society. Chaim Topol plays Tevye, a near broke father of five daughters who refuses to let his fantasy of being rich subside.

There are two strings of change that flow concurrently. The first and the more predominant revolves around the dichotomy of tradition and progressiveness, one Tevye must reluctantly square.

Tevye cherishes tradition. He doesn’t know his customs’ origins, but he won’t deny them. Along with If I was a Rich Man, the film’s opening number which cycles through the Jewish traditions becomes a refrain, a battle-cry for Tevye. However his three eldest daughters have marriage on their mind, and each, by a different means, disrupts the customary flow. The town matchmaker sets up a couple, the father approves it; no more. Tevye has to reconcile his beloved traditions and a forever shifting landscape of relationships.

Topol looks to be having the time of his life in his role. He’s beard-stroking and boisterous, his motions deliberately over-animated (a touch of Ron Moody’s Fagin in his movements) and his voice bellowing with a phoney authority. He’s the affable soul of the film. He’s glowing with paternal warmth and he offers the film’s chief comedic life with his begrudging spouse routine with God, often turning to the Lord and musing when his traditions are shaken, and his seesawing inner ponderings. His is an affectionate performance.

On a surf ace level the film is equally alive and teeming. Oswald Morris’ photography is polished and beautiful, evoking the slick scenery of a Thomas Gainsborough landscape. The wit is crisp, each performance enlivened by a sharp chemistry with its counterparts, and the musical numbers and choreography are indelible and frivolous, adapted to the screen by John Williams and Tom Abbott respectively.

ace level the film is equally alive and teeming. Oswald Morris’ photography is polished and beautiful, evoking the slick scenery of a Thomas Gainsborough landscape. The wit is crisp, each performance enlivened by a sharp chemistry with its counterparts, and the musical numbers and choreography are indelible and frivolous, adapted to the screen by John Williams and Tom Abbott respectively.

It’s a shame them, that when it’s needed, the film’s dramatic tunes never quite ring true.

The second string of change is much bleaker, involving a growing anti-Semitism from the dominant faith, the Jewish community subsequently made an example of.

Perhaps it’s that the film is too jovial for too long for its stakes to ever be taken as seriously as intended. The plight of Tevye and his community is never as involving as one would hope, a surprise given how charming and amicable a personality the characters and the film as a whole possess.

It’s also too long. The film itself is unwilling to part ways with Hollywood’s own tradition of the baggy stage-to-screen adaptation. Whilst it’s never dull, it teases the fringes of tedium, this too making it difficult to be as emotionally involved as the drama requires.

It’s a dissatisfaction made plainer by how stirringly down beat the film’s final thoughts are. It’s a beautiful synthesis of melancholia and hopefulness, a simultaneous rendering of realism and optimism as the Jews face the forlorn music. It’s clear Jewison has a capacity for evocative drama within his film, but it remains that he struggles to fuse lights and darks.

Still, it has such a lively soul, such goodwill. It’s enamouring as a happy-go-lucky Yiddish romp, affectionate and embracing through its unveiling of the purity of a family’s love.

The central metaphor symbolises the gutsy resolve and passion of Tevye himself, shaky in his people’s fears and looming dangers, whilst courageous and beautiful in his navigation of them, like a fiddler on the roof. It’s a similar story for Jewison; there is beauty and warmth in his cinematic melodies, even if he is shaken by the uncertainty of his darker grounds.