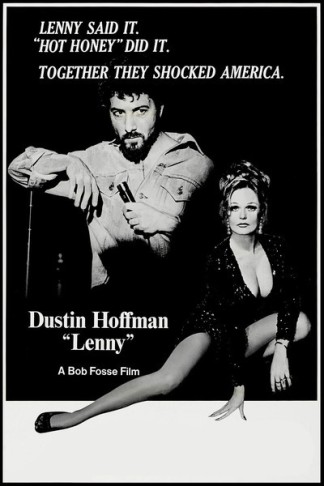

Directed By: Bob Fosse

Written By: Julian Barry (based on his play Lenny)

Starring: Dustin Hoffman, Valerrie Perrine

Late in the film we see Lenny Bruce per form a set half naked and stupefied by drugs. Bob Fosse records the ordeal with an excruciatingly long take, never giving us a chance to turn away as the degenerated Lenny stumbles his way through only a few painful minutes of his set, meandering through a series of thoughts which if expressed with any coherence might have been on the cusp of importance, but as it is add up to nothing. The only laughter elicited is by accident or is out of discomfort from the audience, before the comedian gives up and trudges off. The scene in many ways is an encapsulation of the film as a whole. It’s interestingly made, with a central figure that is for better or for worse transfixing, possessing ideas that are significant, but are expressed without direction or clarity.

form a set half naked and stupefied by drugs. Bob Fosse records the ordeal with an excruciatingly long take, never giving us a chance to turn away as the degenerated Lenny stumbles his way through only a few painful minutes of his set, meandering through a series of thoughts which if expressed with any coherence might have been on the cusp of importance, but as it is add up to nothing. The only laughter elicited is by accident or is out of discomfort from the audience, before the comedian gives up and trudges off. The scene in many ways is an encapsulation of the film as a whole. It’s interestingly made, with a central figure that is for better or for worse transfixing, possessing ideas that are significant, but are expressed without direction or clarity.

Lenny is a biographical drama about said comedian, a puzzled study of a man who was part comedian, part narcissistic social commentator. Dustin Hoffman plays the late Lenny Bruce, at one time a starry eyed, mild mannered young man who transformed into a countercultural rebel through his controversial sets.

Hoffman does a wonderful job of rounding the multiplicities of a very complex man. He is asked to leave no stone unturned in his performance, at one time hopeful and vibrant, to other times broken and wayward; however always passionate. He understands both the significance and faults of the troubled artist.

When we first hear Lenny talk to the audience he highlights his purpose. He wants to liberate words, convey that derogatory terms are only as derogatory as society’s disgust permits them to be. He morphs from geeky, in-over-his-head juvenile impressionist working dives, to a legitimate star and courtroom fixture, a first amendment warrior with a debilitating drug habit, a quietly potent neediness and a mesmerised fan base.

Shot in a newspaper article black and white, his story is revealed to us in a documentary style, where the characters close to him recount his rise and fall. The most significant of which is his on-again-off-again muse Honey (played by Valerie Perrine). An equally hopeful star of the stage, she and Lenny grow quickly infatuated, an innocence driving their dreamy pretences as she too is caught up in the drugs and promiscuity of grimy show business. The film splices snippets of a scraggly Hoffm![Lenny.(1974).Bob_Fosse.Dustin_Hoffman.avi_snapshot_00.29.42_[2012.08.20_17.39.01]](https://filmfracas.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/lenny-1974-bob_fosse-dustin_hoffman-avi_snapshot_00-29-42_2012-08-20_17-39-01.png?w=454&h=252) an performing late in his career, with his tumultuous personal life; his stage used to vent his life’s frustrations, his relationship with the equally implosive Honey an early fixation.

an performing late in his career, with his tumultuous personal life; his stage used to vent his life’s frustrations, his relationship with the equally implosive Honey an early fixation.

It isn’t until Lenny attacks society that his comedic career lifts off. He talks about homosexuality, and black people, and the trigger-happiness of the law. He harasses society’s hypocrisies, becoming a reckless poet; a screwy Jim Morrison , before he sinks into self-absorption.

We get many incarnations of Lenny Bruce in this film, the picture admirable in its respect for the complexities of a clouded mind. The trouble is that Fosse and writer Julian Barry never seem to know what it is they actually want to say about the man. Is he a martyr for free-speech? A self destructive narcissist? Sincere or crass? Fosse is too ambivalent. He gives us three dimensions, but reveals them as vignettes rather than a cohesive whole. Its insights are disparate, the film skipping with abandon between the different phases of Lenny’s life without ever settling on any clear evaluation or thought.

This ambivalence also results in a peculiar lifelessness. It’s a surprise given the amazing energy of Fosse’s awards courter from 2 years prior in Cabaret. If there is a certainty about Lenny it’s that it’s sad, but as was the case with Fosse’s previous depiction of show-business, a film can be bleak but still lively. Lenny’s downbeat undercurrent doesn’t allow its subject to flourish, as though the personality of the man and the film are at odds. The untethered personality of Cabaret was a match for its untethered leading lady; here the fieriness of Lenny is suffocated.

There is a great film buried somewhere in Lenny, but for all its ambition, its range of emotions and fine acting, it feels like a connect-the-dots where the pieces are spaced out over an entire novel. If it were all on the same page it would make an interesting picture, but the image is lost in the scatter.